Mental disorder

| Mental disorder | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Eight women representing prominent mental diagnoses in the nineteenth century. (Armand Gautier) |

|

| ICD-10 | F. |

| MeSH | D001523 |

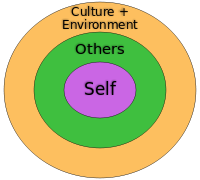

A mental disorder or mental illness is a psychological or behavioral pattern associated with distress or disability that occurs in an individual and is not a part of normal development or culture. The recognition and understanding of mental health conditions has changed over time and across cultures, and there are still variations in the definition, assessment, and classification of mental disorders, although standard guideline criteria are widely accepted.

Currently, mental disorders are conceptualized as disorders of brain circuits likely caused by developmental processes shaped by a complex interplay of genetics and experience.[1] In other words, the genetics of mental illness may really be the genetics of brain development, with different outcomes possible, depending on the biological and environmental context.[1]

Over a third of people in most countries report meeting criteria for the major categories at some point in their life. The causes are often explained in terms of a diathesis-stress model and biopsychosocial model. Services are based in psychiatric hospitals or in the community. Diagnoses are made by psychiatrists or clinical psychologists using various methods, often relying on observation and questioning in interviews. Treatments are provided by various mental health professionals.

Psychotherapy and psychiatric medication are two major treatment options as are social interventions, peer support and self-help. In some cases there may be involuntary detention and involuntary treatment where legislation allows. Stigma and discrimination add to the suffering associated with the disorders, and have led to various social movements campaign for change.

Contents |

Classifications

The definition and classification of mental disorders is a key issue for mental health and for users and providers of mental health services. Most international clinical documents use the term "mental disorder". There are currently two widely established systems that classify mental disorders—ICD-10 Chapter V: Mental and behavioural disorders, part of the International Classification of Diseases produced by the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) produced by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Both list categories of disorder and provide standardized criteria for diagnosis. They have deliberately converged their codes in recent revisions so that the manuals are often broadly comparable, although significant differences remain. Other classification schemes may be used in non-western cultures (see, for example, the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders), and other manuals may be used by those of alternative theoretical persuasions, for example the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual. In general, mental disorders are classified separately to neurological disorders, learning disabilities or mental retardation.

Unlike most of the above systems, some approaches to classification do not employ distinct categories of disorder or dichotomous cut-offs intended to separate the abnormal from the normal. There is significant scientific debate about the different kinds of categorization and the relative merits of categorical versus non-categorical (or hybrid) schemes, with the latter including spectrum, continuum or dimensional systems.

Disorders

There are many different categories of mental disorder, and many different facets of human behavior and personality that can become disordered.[2][3][4][5][6]

Anxiety or fear that interferes with normal functioning may be classified as an anxiety disorder.[7] Commonly recognized categories include specific phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Other affective (emotion/mood) processes can also become disordered. Mood disorder involving unusually intense and sustained sadness, melancholia or despair is known as Major depression or Clinical depression (milder but still prolonged depression can be diagnosed as dysthymia). Bipolar disorder (also known as manic depression) involves abnormally "high" or pressured mood states, known as mania or hypomania, alternating with normal or depressed mood. Whether unipolar and bipolar mood phenomena represent distinct categories of disorder, or whether they usually mix and merge together along a dimension or spectrum of mood, is under debate in the scientific literature.[8]

Patterns of belief, language use and perception can become disordered (e.g. delusions, thought disorder, hallucinations). Psychotic disorders in this domain include schizophrenia, and delusional disorder. Schizoaffective disorder is a category used for individuals showing aspects of both schizophrenia and affective disorders. Schizotypy is a category used for individuals showing some of the characteristics associated with schizophrenia but without meeting cut-off criteria.

Personality—the fundamental characteristics of a person that influence his or her thoughts and behaviors across situations and time—may be considered disordered if judged to be abnormally rigid and maladaptive. Categorical schemes list a number of different such personality disorders, including those sometimes classed as eccentric (e.g. paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders), to those sometimes classed as dramatic or emotional (antisocial, borderline, histrionic or narcissistic personality disorders) or those seen as fear-related (avoidant, dependent, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorders). If an inability to sufficiently adjust to life circumstances begins within three months of a particular event or situation, and ends within six months after the stressor stops or is eliminated, it may instead be classed as an adjustment disorder. There is an emerging consensus that so-called "personality disorders", like personality traits in general, actually incorporate a mixture of acute dysfunctional behaviors that resolve in short periods, and maladaptive temperamental traits that are more stable.[9] Furthermore, there are also non-categorical schemes that rate all individuals via a profile of different dimensions of personality rather than using a cut-off from normal personality variation, for example through schemes based on the Big Five personality traits.[10]

Eating disorders involve disproportionate concern in matters of food and weight.[7] Categories of disorder in this area include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, exercise bulimia or binge eating disorder.

Sleep disorders such as insomnia involve disruption to normal sleep patterns, or a feeling of tiredness despite sleep appearing normal.

Sexual and gender identity disorders may be diagnosed, including dyspareunia, gender identity disorder and ego-dystonic homosexuality. Various kinds of paraphilia are considered mental disorders (sexual arousal to objects, situations, or individuals that are considered abnormal or harmful to the person or others).

People who are abnormally unable to resist certain urges or impulses that could be harmful to themselves or others, may be classed as having an impulse control disorder, including various kinds of tic disorders such as Tourette's syndrome, and disorders such as kleptomania (stealing) or pyromania (fire-setting). Various behavioral addictions, such as gambling addiction, may be classed as a disorder. Obsessive-compulsive disorder can sometimes involve an inability to resist certain acts but is classed separately as being primarily an anxiety disorder.

The use of drugs (legal or illegal), when it persists despite significant problems related to the use, may be defined as a mental disorder termed substance dependence or substance abuse (a broader category than drug abuse). The DSM does not currently use the common term drug addiction and the ICD simply talks about "harmful use". Disordered substance use may be due to a pattern of compulsive and repetitive use of the drug that results in tolerance to its effects and withdrawal symptoms when use is reduced or stopped.

People who suffer severe disturbances of their self-identity, memory and general awareness of themselves and their surroundings may be classed as having a dissociative identity disorder, such as depersonalization disorder or Dissociative Identity Disorder itself (which has also been called multiple personality disorder, or "split personality"). Other memory or cognitive disorders include amnesia or various kinds of old age dementia.

A range of developmental disorders that initially occur in childhood may be diagnosed, for example autism spectrum disorders, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which may continue into adulthood.

Conduct disorder, if continuing into adulthood, may be diagnosed as antisocial personality disorder (dissocial personality disorder in the ICD). Popularist labels such as psychopath (or sociopath) do not appear in the DSM or ICD but are linked by some to these diagnoses.

Disorders appearing to originate in the body, but thought to be mental, are known as somatoform disorders, including somatization disorder and conversion disorder. There are also disorders of the perception of the body, including body dysmorphic disorder. Neurasthenia is an old diagnosis involving somatic complaints as well as fatigue and low spirits/depression, which is officially recognized by the ICD-10 but no longer by the DSM-IV.[11]

Factitious disorders, such as Munchausen syndrome, are diagnosed where symptoms are thought to be experienced (deliberately produced) and/or reported (feigned) for personal gain.

There are attempts to introduce a category of relational disorder, where the diagnosis is of a relationship rather than on any one individual in that relationship. The relationship may be between children and their parents, between couples, or others. There already exists, under the category of psychosis, a diagnosis of shared psychotic disorder where two or more individuals share a particular delusion because of their close relationship with each other.

Various new types of mental disorder diagnosis are occasionally proposed. Among those controversially considered by the official committees of the diagnostic manuals include self-defeating personality disorder, sadistic personality disorder, passive-aggressive personality disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Two recent unique isolated proposals are solastalgia by Glenn Albrecht and hubris syndrome by David Owen. The application of the concept of mental illness to the phenomena described by these authors has in turn been critiqued by Seamus Mac Suibhne.[12]

Causes

Mental disorders can arise from a combination of sources. In many cases there is no single accepted or consistent cause currently established. A common belief even to this day is that disorders result from genetic vulnerabilities exposed by environmental stressors. (see Diathesis-stress model). However, it is clear enough from a simple statistical analysis across the whole spectrum of mental health disorders at least in western cultures that there is a strong relationship between the various forms of severe and complex mental disorder in adulthood and the abuse (physical, sexual or emotional) or neglect of children during the developmental years. Child sexual abuse alone plays a significant role in the causation of a significant percentage of all mental disorders in adult females, most notable examples being eating disorders and borderline personality disorder.

An eclectic or pluralistic mix of models may be used to explain particular disorders, and the primary paradigm of contemporary mainstream Western psychiatry is said to be the biopsychosocial (BPS) model, incorporating biological, psychological and social factors, although this may not always be applied in practice. Biopsychiatry has tended to follow a biomedical model, focusing on "organic" or "hardware" pathology of the brain. Psychoanalytic theories have continued to evolve alongside congitive-behavioural and systemic-family approaches been popular but are now less so. Evolutionary psychology may be used as an overall explanatory theory, and attachment theory is another kind of evolutionary-psychological approach sometimes applied in the context of mental disorders. A distinction is sometimes made between a "medical model" or a "social model" of disorder and disability.

Studies have indicated that genes often play an important role in the development of mental disorders, although the reliable identification of connections between specific genes and specific categories of disorder has proven more difficult. Environmental events surrounding pregnancy and birth have also been implicated. Traumatic brain injury may increase the risk of developing certain mental disorders. There have been some tentative inconsistent links found to certain viral infections,[13] to substance misuse, and to general physical health.

Abnormal functioning of neurotransmitter systems has been implicated, including serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine and glutamate systems. Differences have also been found in the size or activity of certain brain regions in some cases. Psychological mechanisms have also been implicated, such as cognitive (e.g. reason), emotional processes, personality, temperament and coping style.

Social influences have been found to be important, including abuse, bullying and other negative or stressful life experiences. The specific risks and pathways to particular disorders are less clear, however. Aspects of the wider community have also been implicated, including employment problems, socioeconomic inequality, lack of social cohesion, problems linked to migration, and features of particular societies and cultures.

Gender-specific influences

Gender-specific indicators of mental illness incorporate physical or sexual abuse, stress, loss of social network, rape and domestic violence, high progesterone oral contraceptives, and mood disorders during early reproductive years [14]. It is important to note that the intersection of biological, social, and behavioral health problems may result in exacerbated mental health issues. The disproportionate effects of these issues on women’s lives limit their coping skills, leading to negative behaviors such as substance abuse. Finally, these circumstances improve the risk of poor physical health, anxiety, and depression.

Diagnosis

Many mental health professionals, particularly psychiatrists, seek to diagnose individuals by ascertaining their particular mental disorder. Some professionals, for example some clinical psychologists, may avoid diagnosis in favor of other assessment methods such as formulation of a client's difficulties and circumstances.[15] The majority of mental health problems are actually assessed and treated by family physicians during consultations, who may refer on for more specialist diagnosis in acute or chronic cases. Routine diagnostic practice in mental health services typically involves an interview (which may be referred to as a mental status examination), where judgments are made of the interviewee's appearance and behavior, self-reported symptoms, mental health history, and current life circumstances. The views of relatives or other third parties may be taken into account. A physical examination to check for ill health or the effects of medications or other drugs may be conducted. Psychological testing is sometimes used via paper-and-pen or computerized questionnaires, which may include algorithms based on ticking off standardized diagnostic criteria, and in rare specialist cases neuroimaging tests may be requested, but these methods are more commonly found in research studies than routine clinical practice.[16][17] Time and budgetary constraints often limit practicing psychiatrists from conducting more thorough diagnostic evaluations.[18] It has been found that most clinicians evaluate patients using an unstructured, open-ended approach, with limited training in evidence-based assessment methods, and that inaccurate diagnosis may be common in routine practice.[19] Mental illness involving hallucinations or delusions (especially schizophrenia) are prone to misdiagnosis in developing countries due to the presence of psychotic symptoms instigated by nutritional deficiencies. Comorbidity is very common in psychiatric diagnoses, i.e. the same person given a diagnosis in more than one category of disorder.

Management

Treatment and support for mental disorders is provided in psychiatric hospitals, clinics or any of a diverse range of community mental health services. In many countries services are increasingly based on a recovery model that is meant to support each individual's independence, choice and personal journey to regain a meaningful life, although individuals may be treated against their will in a minority of cases. There are a range of different types of treatment and what is most suitable depends on the disorder and on the individual. Many things have been found to help at least some people, and a placebo effect may play a role in any intervention or medication.

Psychotherapy

A major option for many mental disorders is psychotherapy. There are several main types. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is widely used and is based on modifying the patterns of thought and behavior associated with a particular disorder. Psychoanalysis, addressing underlying psychic conflicts and defenses, has been a dominant school of psychotherapy and is still in use. Systemic therapy or family therapy is sometimes used, addressing a network of significant others as well as an individual. Some psychotherapies are based on a humanistic approach. There are a number of specific therapies used for particular disorders, which may be offshoots or hybrids of the above types. Mental health professionals often employ an eclectic or integrative approach. Much may depend on the therapeutic relationship, and there may be problems with trust, confidentiality and engagement.

Medication

A major option for many mental disorders is psychiatric medication and there are several main groups. Antidepressants are used for the treatment of clinical depression as well as often for anxiety and other disorders. Anxiolytics are used for anxiety disorders and related problems such as insomnia. Mood stabilizers are used primarily in bipolar disorder. Antipsychotics are mainly used for psychotic disorders, notably for positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Stimulants are commonly used, notably for ADHD.

Despite the different conventional names of the drug groups, there may be considerable overlap in the disorders for which they are actually indicated, and there may also be off-label use of medications. There can be problems with adverse effects of medication and adherence to them, and there is also criticism of pharmaceutical marketing and professional conflicts of interest.

Other

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is sometimes used in severe cases when other interventions for severe intractable depression have failed. Psychosurgery is considered experimental but is advocated by certain neurologists in certain rare cases.[20][21]

Counseling (professional) and co-counseling (between peers) may be used. Psychoeducation programs may provide people with the information to understand and manage their problems. Creative therapies are sometimes used, including music therapy, art therapy or drama therapy. Lifestyle adjustments and supportive measures are often used, including peer support, self-help groups for mental health and supported housing or supported employment (including social firms). Some advocate dietary supplements.[22]

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the disorder, the individual and numerous related factors. Some disorders are transient, while others may last a lifetime. Some disorders may be very limited in their functional effects, while others may involve substantial disability and support needs. The degree of ability or disability may vary across different life domains. Continued disability has been linked to institutionalization, discrimination and social exclusion as well as to the inherent properties of disorders.

Even those disorders often considered the most serious and intractable have varied courses. Long-term international studies of schizophrenia have found that over a half of individuals recover in terms of symptoms, and around a fifth to a third in terms of symptoms and functioning, with some requiring no medication. At the same time, many have serious difficulties and support needs for many years, although "late" recovery is still possible. The World Health Organization concluded that the long-term studies' findings converged with others in "relieving patients, carers and clinicians of the chronicity paradigm which dominated thinking throughout much of the 20th century."[23][24] Around half of people initially diagnosed with bipolar disorder achieve syndromal recovery (no longer meeting criteria for the diagnosis) within six weeks, and nearly all achieve it within two years, with nearly half regaining their prior occupational and residential status in that period. However, nearly half go on to experience a new episode of mania or major depression within the next two years.[25] Functioning has been found to vary, being poor during periods of major depression or mania but otherwise fair to good, and possibly superior during periods of hypomania in Bipolar II.[26]

Some mental disorders are linked, on average, to increased rates of attempted and/or completed suicide or self-harm.

Despite often being characterized in purely negative terms, some mental states labeled as disorders can also involve above-average creativity, non-conformity, goal-striving, meticulousness, or empathy.[27] In addition, the public perception of the level of disability associated with mental disorders can change.[28]

Epidemiology

Mental disorders are common. World wide more than one in three people in most countries report sufficient criteria for at least one at some point in their life.[29] In the United States 46% qualifies for a mental illness at some point.[30] An ongoing survey indicates that anxiety disorders are the most common in all but one country, followed by mood disorders in all but two countries, while substance disorders and impulse-control disorders were consistently less prevalent.[31] Rates varied by region.[32] Such statistics are widely believed to be underestimates, due to poor diagnosis (especially in countries without affordable access to mental health services) and low reporting rates, in part because of the predominant use of self-report data rather than semi-structured instruments. Actual lifetime prevalence rates for mental disorders are estimated to be between 65% and 85%.

A review of anxiety disorder surveys in different countries found average lifetime prevalence estimates of 16.6%, with women having higher rates on average.[33] A review of mood disorder surveys in different countries found lifetime rates of 6.7% for major depressive disorder (higher in some studies, and in women) and 0.8% for Bipolar I disorder.[34]

In the United States the frequency of disorder is: anxiety disorder (28.8%), mood disorder (20.8%), impulse-control disorder (24.8%) or substance use disorder (14.6%).[35][36][37]

A 2004 cross-Europe study found that approximately one in four people reported meeting criteria at some point in their life for at least one of the DSM-IV disorders assessed, which included mood disorders (13.9%), anxiety disorders (13.6%) or alcohol disorder (5.2%). Approximately one in ten met criteria within a 12-month period. Women and younger people of either gender showed more cases of disorder.[38] A 2005 review of surveys in 16 European countries found that 27% of adult Europeans are affected by at least one mental disorder in a 12 month period.[39]

An international review of studies on the prevalence of schizophrenia found an average (median) figure of 0.4% for lifetime prevalence; it was consistently lower in poorer countries.[40]

Studies of the prevalence of personality disorders (PDs) have been fewer and smaller-scale, but one broad Norwegian survey found a five-year prevalence of almost 1 in 7 (13.4%). Rates for specific disorders ranged from 0.8% to 2.8%, differing across countries, and by gender, educational level and other factors.[41] A US survey that incidentally screened for personality disorder found a rate of 14.79%.[42]

Approximately 7% of a preschool pediatric sample were given a psychiatric diagnosis in one clinical study, and approximately 10% of 1- and 2-year-olds receiving developmental screening have been assessed as having significant emotional/behavioral problems based on parent and pediatrician reports.[43]

While rates of psychological disorders are the same for men and women, women have twice the rate of depression than men [44]. Each year 73 million women are afflicted with major depression, and suicide is ranked 7th as the cause of death for women between the ages of 20-59. Depressive disorders account for close to 41.9% of the disability from neuropsychiatric disorders among women compared to 29.3% among men. [45].

History

Ancient civilizations

Ancient civilizations described and treated a number of mental disorders. The Greeks coined terms for melancholy, hysteria and phobia and developed the humorism theory. Psychiatric theories and treatments developed in Persia, Arabia and the Muslim Empire, particularly in the medieval Islamic world from the 8th century, where the first psychiatric hospitals were built.

Europe

Middle Ages

Conceptions of madness in the Middle Ages in Christian Europe were a mixture of the divine, diabolical, magical and humoral, as well as more down to earth considerations. In the early modern period, some people with mental disorders may have been victims of the witch-hunts but were increasingly admitted to local workhouses and jails or sometimes to private madhouses. Many terms for mental disorder that found their way into everyday use first became popular in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Eighteenth century

By the end of the 17th century and into the Enlightenment, madness was increasingly seen as an organic physical phenomenon with no connection to the soul or moral responsibility. Asylum care was often harsh and treated people like wild animals, but towards the end of the 18th century a moral treatment movement gradually developed. Clear descriptions of some syndromes may be rare prior to the 1800s.

Nineteenth century

Industrialization and population growth led to a massive expansion of the number and size of insane asylums in every Western country in the 19th century. Numerous different classification schemes and diagnostic terms were developed by different authorities, and the term psychiatry was coined, though medical superintendents were still known as alienists.

Twentieth century

The turn of the 20th century saw the development of psychoanalysis, which would later come to the fore, along with Kraepelin's classification scheme. Asylum "inmates" were increasingly referred to as "patients", and asylums renamed as hospitals.

Europe and the U.S.

In the twentieth century in the United States, a mental hygiene movement developed, aiming to prevent mental disorders. Clinical psychology and social work developed as professions. World War I saw a massive increase of conditions that came to be termed "shell shock".

World War II saw the development in the U.S. of a new psychiatric manual for categorizing mental disorders, which along with existing systems for collecting census and hospital statistics led to the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) followed suit with a section on mental disorders. The term stress, having emerged out of endocrinology work in the 1930s, was increasingly applied to mental disorders.

Electroconvulsive therapy, insulin shock therapy, lobotomies and the "neuroleptic" chlorpromazine came to be used by mid-century. An antipsychiatry movement came to the fore in the 1960s. Deinstitutionalization gradually occurred in the West, with isolated psychiatric hospitals being closed down in favor of community mental health services. A consumer/survivor movement gained momentum. Other kinds of psychiatric medication gradually came into use, such as "psychic energizers" and lithium. Benzodiazepines gained widespread use in the 1970s for anxiety and depression, until dependency problems curtailed their popularity.

Advances in neuroscience and genetics led to new research agendas. Cognitive behavioral therapy was developed. The DSM and then ICD adopted new criteria-based classifications, and the number of "official" diagnoses saw a large expansion. Through the 1990s, new SSRI antidepressants became some of the most widely prescribed drugs in the world. Also during the 1990s, a recovery model developed.

Society and culture

Different societies or cultures and even different individuals in a culture can disagree as to what constitutes optimal versus pathological biological and psychological functioning. Research has demonstrated that cultures vary in the relative importance placed on, for example, happiness, autonomy, or social relationships for pleasure. Likewise, the fact that a behavior pattern is valued, accepted, encouraged, or even statistically normative in a culture does not necessarily mean that it is conducive to optimal psychological functioning.

People in all cultures find some behaviors bizarre or even incomprehensible. But just what they feel is bizarre or incomprehensible is ambiguous and subjective.[46] These differences in determination can become highly contentious.

The process by which conditions and difficulties come to be defined and treated as medical conditions and problems, and thus come under the authority of doctors and other health professionals, is known as medicalization or pathologization.

In the scientific and academic literature on the definition or classification of mental disorder, one extreme argues that it is entirely a matter of value judgements (including of what is normal) while another proposes that it is or could be entirely objective and scientific (including by reference to statistical norms).[47] Common hybrid views argue that the concept of mental disorder is objective but a "fuzzy prototype" that can never be precisely defined, or alternatively that it inevitably involves a mix of scientific facts and subjective value judgments.[48]

Professions and fields

A number of professions have developed that specialize in the treatment of mental disorders, including the medical speciality of psychiatry (including psychiatric nursing),[49][50][51] a subset of psychology known as clinical psychology,[52] social work,[53] as well as mental health counselors, marriage and family therapists, psychotherapists, counselors and public health professionals. Those with personal experience of using mental health services are also increasingly involved in researching and delivering mental health services and working as mental health professionals.[54][55][56][57] The different clinical and scientific perspectives draw on diverse fields of research and theory, and different disciplines may favor differing models, explanations and goals.[27]

Movements

The consumer/survivor movement (also known as user/survivor movement) is made up of individuals (and organizations representing them) who are clients of mental health services or who consider themselves "survivors" of mental health services. The movement campaigns for improved mental health services and for more involvement and empowerment within mental health services, policies and wider society.[58][59][60] Patient advocacy organizations have expanded with increasing deinstitutionalization in developed countries, working to challenge the stereotypes, stigma and exclusion associated with psychiatric conditions. An antipsychiatry movement fundamentally challenges mainstream psychiatric theory and practice, including asserting that psychiatric diagnoses of mental illnesses are neither real nor useful.[61][62][63]

Intangible experiences

Religious, spiritual, or transpersonal experiences and beliefs are typically not defined as disordered, especially if widely shared, despite meeting many criteria of delusional or psychotic disorders.[64][65] Even when a belief or experience can be shown to produce distress or disability—the ordinary standard for judging mental disorders—the presence of a strong cultural basis for that belief, experience, or interpretation of experience, generally disqualifies it from counting as evidence of mental disorder.

Western bias

Current diagnostic guidelines have been criticized as having a fundamentally Euro-American outlook. They have been widely implemented, but opponents argue that even when diagnostic criteria are accepted across different cultures, it does not mean that the underlying constructs have any validity within those cultures; even reliable application can prove only consistency, not legitimacy.[66]

Advocating a more culturally sensitive approach, critics such as Carl Bell and Marcello Maviglia contend that the cultural and ethnic diversity of individuals is often discounted by researchers and service providers.[67]

Cross-cultural psychiatrist Arthur Kleinman contends that the Western bias is ironically illustrated in the introduction of cultural factors to the DSM-IV: that disorders or concepts from non-Western or non-mainstream cultures are described as "culture-bound", whereas standard psychiatric diagnoses are given no cultural qualification whatsoever, reveals to Kleinman an underlying assumption that Western cultural phenomena are universal.[68] Kleinman's negative view towards the culture-bound syndrome is largely shared by other cross-cultural critics, common responses included both disappointment over the large number of documented non-Western mental disorders still left out and frustration that even those included were often misinterpreted or misrepresented.[69]

Many mainstream psychiatrists are dissatisfied with the new culture-bound diagnoses, although for different reasons. Robert Spitzer, a lead architect of the DSM-III, has hypothesized that adding cultural formulations was an attempt to appease cultural critics and stated that the formulations lack any scientific motivation or support. Spitzer also posits that the new culture-bound diagnoses are rarely used, maintaining that the standard diagnoses apply regardless of the culture involved. In general, mainstream psychiatric opinion remains that if a diagnostic category is valid, cross-cultural factors are either irrelevant or are significant only to specific symptom presentations.[66]

Relationships and morality

Clinical conceptions of mental illness also overlap with personal and cultural values in the domain of morality, so much so that it is sometimes argued that separating the two is impossible without fundamentally redefining the essence of being a particular person in a society.[70] In clinical psychiatry, persistent distress and disability indicate an internal disorder requiring treatment; but in another context, that same distress and disability can be seen as an indicator of emotional struggle and the need to address social and structural problems.[71][72] This dichotomy has lead some academics and clinicians to advocate a postmodernist conceptualization of mental distress and well-being.[73][74]

Such approaches, along with cross-cultural and "heretical" psychologies centered on alternative cultural and ethnic and race-based identities and experiences, stand in contrast to the mainstream psychiatric community's active avoidance of any involvement with either morality or culture.[75] In many countries there are attempts to challenge perceived prejudice against minority groups, including alleged institutional racism within psychiatric services.[76]

Laws and policies

Three quarters of countries around the world have mental health legislation. Compulsory admission to mental health facilities (also known as involuntary commitment or sectioning), is a controversial topic. From some points of view it can impinge on personal liberty and the right to choose, and carry the risk of abuse for political, social and other reasons; from other points of view, it can potentially prevent harm to self and others, and assist some people in attaining their right to healthcare when unable to decide in their own interests.[77]

All human-rights oriented mental health laws require proof of the presence of a mental disorder as defined by internationally accepted standards, but the type and severity of disorder that counts can vary in different jurisdictions. The two most often utilized grounds for involuntary admission are said to be serious likelihood of immediate or imminent danger to self or others, and the need for treatment. Applications for someone to be involuntarily admitted may usually come from a mental health practitioner, a family member, a close relative, or a guardian. Human-rights-oriented laws usually stipulate that independent medical practitioners or other accredited mental health practitioners must examine the patient separately and that there should be regular, time-bound review by an independent review body.[77] An individual must be shown to lack the capacity to give or withhold informed consent (i.e. to understand treatment information and its implications). Legal challenges in some areas have resulted in supreme court decisions that a person does not have to agree with a psychiatrist's characterization of their issues as an "illness", nor with a psychiatrist's conviction in medication, but only recognize the issues and the information about treatment options.[78]

Proxy consent (also known as substituted decision-making) may be given to a personal representative, a family member or a legally appointed guardian, or patients may have been able to enact an advance directive as to how they wish to be treated.[77] The right to supported decision-making may also be included in legislation.[79] Involuntary treatment laws are increasingly extended to those living in the community, for example outpatient commitment laws (known by different names) are used in New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom and most of the United States.

The World Health Organization reports that in many instances national mental health legislation takes away the rights of persons with mental disorders rather than protecting rights, and is often outdated.[77] In 1991, the United Nations adopted the Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care, which established minimum human rights standards of practice in the mental health field. In 2006, the UN formally agreed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to protect and enhance the rights and opportunities of disabled people, including those with psychosocial disabilities.[80]

The term insanity, sometimes used colloquially as a synonym for mental illness, is often used technically as a legal term. The insanity defense may be used in a legal trial (known as the mental disorder defence in some countries).

Perception and discrimination

- Stigma

The social stigma associated with mental disorders is a widespread problem. Some people believe those with serious mental illnesses cannot recover, or are to blame for problems.[81] The US Surgeon General stated in 1999 that: "Powerful and pervasive, stigma prevents people from acknowledging their own mental health problems, much less disclosing them to others."[82] Employment discrimination is reported to play a significant part in the high rate of unemployment among those with a diagnosis of mental illness.[83]

Efforts are being undertaken worldwide to eliminate the stigma of mental illness,[84] although their methods and outcomes have sometimes been criticized.[85]

A 2008 study by Baylor University researchers found that clergy in the US often deny or dismiss the existence of a mental illness. Of 293 Christian church members, more than 32 percent were told by their church pastor that they or their loved one did not really have a mental illness, and that the cause of their problem was solely spiritual in nature, such as a personal sin, lack of faith or demonic involvement. The researchers also found that women were more likely than men to get this response. All participants in both studies were previously diagnosed by a licensed mental health provider as having a serious mental illness.[86] However, there is also research suggesting that people are often helped by extended families and supportive religious leaders who listen with kindness and respect, which can often contrast with usual practice in psychiatric diagnosis and medication.[87]

- Media and general public

Media coverage of mental illness comprises predominantly negative depictions, for example, of incompetence, violence or criminality, with far less coverage of positive issues such as accomplishments or human rights issues.[88][89][90] Such negative depictions, including in children's cartoons, are thought to contribute to stigma and negative attitudes in the public and in those with mental health problems themselves, although more sensitive or serious cinematic portrayals have increased in prevalence.[91][92]

In the United States, the Carter Center has created fellowships for journalists in South Africa, the U.S., and Romania, to enable reporters to research and write stories on mental health topics.[93] Former US First Lady Rosalynn Carter began the fellowships not only to train reporters in how to sensitively and accurately discuss mental health and mental illness, but also to increase the number of stories on these topics in the news media.[94][95] There is a World Mental Health Day, which the US and Canada subsume under a Mental Illness Awareness Week.

The general public have been found to hold a strong stereotype of dangerousness and desire for social distance from individuals described as mentally ill.[96] A US national survey found that a higher percentage of people rate individuals described as displaying the characteristics of a mental disorder as "likely to do something violent to others", compared to the percentage of people who are rating individuals described as being "troubled".[97]

- Violence

Despite public or media opinion, national studies have indicated that severe mental illness does not independently predict future violent behavior, on average, and is not a leading cause of violence in society. There is a statistical association with various factors that do relate to violence (in anyone), such as substance abuse and various personal, social and economic factors.[98]

In fact, findings consistently indicate that it is many times more likely that people diagnosed with a serious mental illness living in the community will be the victims rather than the perpetrators of violence.[99][100] In a study of individuals diagnosed with "severe mental illness" living in a US inner-city area, a quarter were found to have been victims of at least one violent crime over the course of a year, a proportion eleven times higher than the inner-city average, and higher in every category of crime including violent assaults and theft.[101] People with a diagnosis may find it more difficult to secure prosecutions, however, due in part to prejudice and being seen as less credible.[102]

However, there are some specific diagnoses, such as childhood conduct disorder or adult antisocial personality disorder or psychopathy, which are defined by or inherently associated with conduct problems and violence. There are conflicting findings about the extent to which certain specific symptoms, notably some kinds of psychosis (hallucinations or delusions) that can occur in disorders such as schizophrenia, delusional disorder or mood disorder, are linked to an increased risk of serious violence on average. The mediating factors of violent acts, however, are most consistently found to be mainly socio-demographic and socio-economic factors such as being young, male, of lower socioeconomic status and, in particular, substance abuse (including alcoholism) to which some people may be particularly vulnerable.[27][99][103][104]

High-profile cases have led to fears that serious crimes, such as homicide, have increased due to deinstitutionalization, but the evidence does not support this conclusion.[104][105] Violence that does occur in relation to mental disorder (against the mentally ill or by the mentally ill) typically occurs in the context of complex social interactions, often in a family setting rather than between strangers.[106] It is also an issue in health care settings[107] and the wider community.[108]

In animals

Psychopathology in non-human primates has been studied since the mid 20th century. Over 20 behavioral patterns in captive chimpanzees have been documented as (statistically) abnormal for their frequency, severity or oddness—some of which have also been observed in the wild. Captive great apes show gross behavioral abnormalities such as stereotypy of movements, self-mutilation, disturbed emotional reactions (mainly fear or aggression) towards companions, lack of species-typical communications, and generalized learned helplessness. In some cases such behaviors are hypothesized to be equivalent to symptoms associated with psychiatric disorders in humans such as depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder. Concepts of antisocial, borderline and schizoid personality disorders have also been applied to non-human great apes.[109]

The risk of anthropomorphism is often raised with regard to such comparisons, and assessment of non-human animals cannot incorporate evidence from linguistic communication. However, available evidence may range from nonverbal behaviors—including physiological responses and homologous facial displays and acoustic utterances—to neurochemical studies. It is pointed out that human psychiatric classification is often based on statistical description and judgement of behaviors (especially when speech or language is impaired) and that the use of verbal self-report is itself problematic and unreliable.[109][110]

Psychopathology has generally been traced, at least in captivity, to adverse rearing conditions such as early separation of infants from mothers; early sensory deprivation; and extended periods of social isolation. Studies have also indicated individual variation in temperament, such as sociability or impulsiveness. Particular causes of problems in captivity have included integration of strangers into existing groups and a lack of individual space, in which context some pathological behaviors have also been seen as coping mechanisms. Remedial interventions have included careful individually tailored re-socialization programs, behavior therapy, environment enrichment, and on rare occasions psychiatric drugs. Socialization has been found to work 90% of the time in disturbed chimpanzees, although restoration of functional sexuality and care-giving is often not achieved.[109][111]

Laboratory researchers sometimes try to develop animal models of human mental disorders, including by inducing or treating symptoms in animals through genetic, neurological, chemical or behavioral manipulation,[112][113] but this has been criticized on empirical grounds[114] and opposed on animal rights grounds.

See also

- Abnormal psychology

- List of mental disorders as defined by the DSM and ICD

- Mental health

- Music therapy

- Psychopathology

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Insel, T.R., Wang, P.S. (2010). Rethinking mental illness. JAMA, 303, 1970-1971.

- ↑ Gazzaniga, M.S., & Heatherton, T.F. (2006). Psychological Science. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- ↑ WebMD Inc (2005, July 01). Mental Health: Types of Mental Illness. Retrieved April 19, 2007, from http://www.webmd.com/mental-health/mental-health-types-illness

- ↑ United States Department of Health & Human Services. (1999). Overview of Mental Illness. Retrieved April 19, 2007

- ↑ NIMH (2005) Teacher's Guide: Information about Mental Illness and the Brain Curriculum supplement from The NIH Curriculum Supplements Series

- ↑ Phillip W. Long M.D. (1995-2008). "Disorders". Internet Mental Health. http://www.mentalhealth.com/p20-grp.html. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Mental Health: Types of Mental Illness". WebMD. http://www.webmd.com/mental-health/mental-health-types-illness. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ↑ Akiskal HS, Benazzi F (May 2006). "The DSM-IV and ICD-10 categories of recurrent [major] depressive and bipolar II disorders: evidence that they lie on a dimensional spectrum". J Affect Disord 92 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.035. PMID 16488021.

- ↑ Clark LA (2007). "Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorder: perennial issues and an emerging reconceptualization". Annu Rev Psychol 58: 227–57. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190200. PMID 16903806. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190200.

- ↑ Morey LC, Hopwood CJ, Gunderson JG, et al. (July 2007). "Comparison of alternative models for personality disorders". Psychol Med 37 (7): 983–94. doi:10.1017/S0033291706009482. PMID 17121690.

- ↑ Gamma A, Angst J, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W (March 2007). "The spectra of neurasthenia and depression: course, stability and transitions". Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 257 (2): 120–7. doi:10.1007/s00406-006-0699-6. PMID 17131216.

- ↑ Mac Suibhne, S. (2009). "What makes “a new mental illness”?: The cases of solastalgia and hubris syndrome". Cosmos and History 5 (2): 210–225.

- ↑ Yolken RH, Torrey EF (01 January 1995). "Viruses, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder". Clin Microbiol Rev. 8 (1): 131–45. PMID 7704891. PMC 172852. http://cmr.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7704891.

- ↑ www.womenshealth.about.com

- ↑ Kinderman P, Lobban F (2000). "Evolving formulations: Sharing complex information with clients". Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy 28 (3): 307–10. doi:10.1017/S1352465800003118.

- ↑ HealthWise (2004) Mental Health Assessment. Yahoo! Health

- ↑ Davies T (May 1997). "ABC of mental health. Mental health assessment". BMJ 314 (7093): 1536–9. PMID 9183204. PMC 2126757. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/314/7093/1536.

- ↑ Kashner TM, Rush AJ, Surís A, et al. (May 2003). "Impact of structured clinical interviews on physicians' practices in community mental health settings". Psychiatr Serv 54 (5): 712–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.712. PMID 12719503. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12719503.

- ↑ Shear MK, Greeno C, Kang J, et al. (April 2000). "Diagnosis of nonpsychotic patients in community clinics". Am J Psychiatry 157 (4): 581–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.581. PMID 10739417. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10739417.

- ↑ Mind Disorders Encyclopedia Psychosurgery [Retrieved on August 5th 2008]

- ↑ Mashour GA, Walker EE, Martuza RL (June 2005). "Psychosurgery: past, present, and future" (PDF). Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 48 (3): 409–19. doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.09.002. PMID 15914249. http://dura.stanford.edu/Articles/Psychosurgery.pdf.

- ↑ Lakhan SE, Vieira KF (2008). "Nutritional therapies for mental disorders". Nutr J 7: 2. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-7-2. PMID 18208598. PMC 2248201. http://www.nutritionj.com/content/7/1/2.

- ↑ Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. (June 2001). "Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study". Br J Psychiatry 178: 506–17. doi:10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. PMID 11388966. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11388966. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ Jobe TH, Harrow M (December 2005). "Long-term outcome of patients with schizophrenia: a review" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50 (14): 892–900. PMID 16494258. http://ww1.cpa-apc.org:8080/Publications/Archives/CJP/2005/december/cjp-dec-05-Harrow-IR.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ↑ Tohen M, Zarate CA, Hennen J, et al. (December 2003). "The McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study: prediction of recovery and first recurrence". Am J Psychiatry 160 (12): 2099–107. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2099. PMID 14638578. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/160/12/2099.

- ↑ Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. (December 2005). "Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: a prospective, comparative, longitudinal study" (PDF). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 (12): 1322–30. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1322. PMID 16330720. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/reprint/62/12/1322.pdf.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Pilgrim, David; Rogers, Anne (2005). A sociology of mental health and illness (3rd ed.). [Milton Keynes]: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-21583-1.

- ↑ Ferney, V. (2003) The Hierarchy of Mental Illness: Which diagnosis is the least debilitating? New York City Voices Jan/March

- ↑ WHO International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology (2000) Cross-national comparisons of the prevalences and correlates of mental disorders Bulletin of the World Health Organization v.78 n.4

- ↑ Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (June 2005). "Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 (6): 593–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. PMID 15939837.

- ↑ "The World Mental Health Survey Initiative". http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/index.php.

- ↑ Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. (June 2004). "Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys". JAMA 291 (21): 2581–90. doi:10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. PMID 15173149.

- ↑ Somers JM, Goldner EM, Waraich P, Hsu L (February 2006). "Prevalence and incidence studies of anxiety disorders: a systematic review of the literature". Can J Psychiatry 51 (2): 100–13. PMID 16989109. http://ww1.cpa-apc.org:8080/Publications/Archives/CJP/2004/february/waraich.asp.

- ↑ Waraich P, Goldner EM, Somers JM, Hsu L (February 2004). "Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: a systematic review of the literature". Can J Psychiatry 49 (2): 124–38. PMID 15065747. http://ww1.cpa-apc.org:8080/Publications/Archives/CJP/2004/february/waraich.asp.

- ↑ Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (June 2005). "Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 (6): 593–602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. PMID 15939837.

- ↑ Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (June 2005). "Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 (6): 617–27. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. PMID 15939839.

- ↑ US National Institute of Mental Health (2006) The Numbers Count: Mental Disorders in America Retrieved May 2007

- ↑ Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. (2004). "Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project". Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 109 (420): 21–7. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00327.x. PMID 15128384.

- ↑ Wittchen HU, Jacobi F (August 2005). "Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe—a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15 (4): 357–76. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.012. PMID 15961293.

- ↑ Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J (May 2005). "A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia". PLoS Med. 2 (5): e141. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141. PMID 15916472.

- ↑ Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V (June 2001). "The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 58 (6): 590–6. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590. PMID 11386989. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11386989.

- ↑ Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, et al. (July 2004). "Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions". J Clin Psychiatry 65 (7): 948–58. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0711. PMID 15291684. http://article.psychiatrist.com/?ContentType=START&ID=10000967.

- ↑ Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Davis NO (January 2004). "Assessment of young children's social-emotional development and psychopathology: recent advances and recommendations for practice". J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45 (1): 109–34. doi:10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00316.x. PMID 14959805. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0021-9630&date=2004&volume=45&issue=1&spage=109.

- ↑ www.nami.org

- ↑ http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/

- ↑ Heinimaa M (October 2002). "Incomprehensibility: the role of the concept in DSM-IV definition of schizophrenic delusions". Med Health Care Philos 5 (3): 291–5. doi:10.1023/A:1021164602485. PMID 12517037. http://www.kluweronline.com/art.pdf?issn=1386-7423&volume=5&page=291.

- ↑ Berrios G E (April 1999). "Classifications in psychiatry: a conceptual history". Aust N Z J Psychiatry 33 (2): 145–60. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.1999.00555.x. PMID 10336212. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0004-8674&date=1999&volume=33&issue=2&spage=145.

- ↑ Perring, C. (2005) Mental Illness Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Andreasen NC (1 May 1997). "What is psychiatry?". Am J Psychiatry 154 (5): 591–3. PMID 9137110. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9137110.

- ↑ University of Melbourne. (2005, August 19). What is Psychiatry?. Retrieved April 19, 2007, from http://www.psychiatry.unimelb.edu.au/info/what_is_psych.html

- ↑ California Psychiatric Association. (2007, February 28). Frequently Asked Questions About Psychiatry & Psychiatrists. Retrieved April 19, 2007, from http://www.calpsych.org/publications/cpa/faqs.html

- ↑ American Psychological Association, Division 12, http://www.apa.org/divisions/div12/aboutcp.html

- ↑ Golightley, M. (2004) Social work and Mental Health Learning Matters, UK

- ↑ Goldstrom ID, Campbell J, Rogers JA, et al. (January 2006). "National estimates for mental health mutual support groups, self-help organizations, and consumer-operated services". Adm Policy Ment Health 33 (1): 92–103. doi:10.1007/s10488-005-0019-x. PMID 16240075. http://www.springerlink.com/content/u132325343qlw4r0/.

- ↑ The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (1998) The experiences of mental health service users as mental health professionals

- ↑ Chamberlin J (2005). "User/consumer involvement in mental health service delivery". Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 14 (1): 10–4. PMID 15792289.

- ↑ Terence V. McCann, John Baird, Eileen Clark, Sai Lu (2006) Beliefs about using consumer consultants in inpatient psychiatric units International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 15 (4), 258–265.

- ↑ Everett B (1994). "Something is happening: the contemporary consumer and psychiatric survivor movement in historical context". Journal of Mind and Behavior 15 (1-2): 55–7. http://www.umaine.edu/JMB/archives/volume15/15_1-2_1994winterspring.html#abstract4.

- ↑ Rissmiller DJ, Rissmiller JH (June 2006). "Evolution of the antipsychiatry movement into mental health consumerism". Psychiatr Serv 57 (6): 863–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.6.863. PMID 16754765.

- ↑ Oaks D (August 2006). "The evolution of the consumer movement". Psychiatr Serv 57 (8): 1212; author reply 1216. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.57.8.1212. PMID 16870979. http://psychservices.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/57/8/1212.

- ↑ The Antipsychiatry Coalition. (2005, November 26). The Antipsychiatry Coalition. Retrieved April 19, 2007, from www.antipsychiatry.org

- ↑ O'Brien AP, Woods M, Palmer C (March 2001). "The emancipation of nursing practice: applying anti-psychiatry to the therapeutic community". Aust N Z J Ment Health Nurs 10 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0979.2001.00183.x. PMID 11421968. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1440-0979.2001.00183.x.

- ↑ Weitz D (2003). "Call me antipsychiatry activist—not "consumer"". Ethical Hum Sci Serv 5 (1): 71–2. PMID 15279009.

- ↑ Pierre JM (May 2001). "Faith or delusion? At the crossroads of religion and psychosis". J Psychiatr Pract 7 (3): 163–72. doi:10.1097/00131746-200105000-00004. PMID 15990520. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=1527-4160&volume=7&issue=3&spage=163.

- ↑ Johnson CV, Friedman HL (2008). "Enlightened or Delusional? Differentiating Religious, Spiritual, and Transpersonal Experiences from Psychopathology". Journal of Humanistic Psychology 48 (4): 505–27. doi:10.1177/0022167808314174. http://jhp.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/48/4/505.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Widiger TA, Sankis LM (2000). "Adult psychopathology: issues and controversies". Annu Rev Psychol 51: 377–404. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.377. PMID 10751976.

- ↑ Shankar Vedantam, Psychiatry's Missing Diagnosis: Patients' Diversity Is Often Discounted Washington Post: Mind and Culture, June 26

- ↑ Kleinman A (1997). "Triumph or pyrrhic victory? The inclusion of culture in DSM-IV". Harv Rev Psychiatry 4 (6): 343–4. doi:10.3109/10673229709030563. PMID 9385013.

- ↑ Bhugra, D. & Munro, A. (1997) Troublesome Disguises: Underdiagnosed Psychiatric Syndromes Blackwell Science Ltd

- ↑ Clark LA (2006). "The role of moral judgment in personality disorder diagnosis". J Pers Disord. 20 (2): 184–5. doi:10.1521/pedi.2006.20.2.184.

- ↑ Karasz A (April 2005). "Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression". Social Science in Medicine 60 (7): 1625–35. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.011. PMID 15652693.

- ↑ Tilbury, F., Rapley, M. (2004) 'There are orphans in Africa still looking for my hands': African women refugees and the sources of emotional distress Health Sociology Review. Vol 13, Issue 1, 54–64

- ↑ Bracken P, Thomas P (March 2001). "Postpsychiatry: a new direction for mental health". BMJ 322 (7288): 724–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7288.724. PMID 11264215. PMC 1119907. http://bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11264215.

- ↑ Lewis B (2000). "Psychiatry and Postmodern Theory". J Med Humanit 21 (2): 71–84. doi:10.1023/A:1009018429802. http://www.springerlink.com/link.asp?id=j75517g14h618189.

- ↑ Kwate NO (2005). "The heresy of African-centered psychology". J Med Humanit 26 (4): 215–35. doi:10.1007/s10912-005-7698-x. PMID 16333686.

- ↑ Commentary on institutional racism in psychiatry, 2007

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 77.3 World Health Organization (2005) WHO Resource Book on Mental Health: Human rights and legislation ISBN 924156282 (PDF)

- ↑ Sklar R (June 2007). "Starson v. Swayze: the Supreme Court speaks out (not all that clearly) on the question of "capacity"". Can J Psychiatry 52 (6): 390–6. PMID 17696026.

- ↑ Manitoba Family Services and Housing. The Vulnerable Persons Living with a Mental Disability Act, 1996

- ↑ ENABLE website UN section on disability

- ↑ CAMH: Toronto Star Opinion Editorial: Ending stigma of mental illness

- ↑ Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General - Chapter 8

- ↑ Stuart H (September 2006). "Mental illness and employment discrimination". Curr Opin Psychiatry 19 (5): 522–6. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000238482.27270.5d. PMID 16874128. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/542517.

- ↑ Stop Stigma

- ↑ Read J, Haslam N, Sayce L, Davies E (November 2006). "Prejudice and schizophrenia: a review of the 'mental illness is an illness like any other' approach". Acta Psychiatr Scand 114 (5): 303–18. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00824.x. PMID 17022790.

- ↑ Study Finds Serious Mental Illness Often Dismissed by Local Church Newswise, Retrieved on October 15, 2008.

- ↑ Psychiatric diagnoses are less reliable than star signs Times Online, June 2009

- ↑ Coverdate J, Nairn R, Claasen D (2001). "Depictions of mental illness in print media: a prospective national sample". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 36 (5): 697–700. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.00998.x. PMID 12225457. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.00998.x.

- ↑ Edney, RD. (2004) Mass Media and Mental Illness: A Literature Review Canadian Mental Health Association

- ↑ Diefenbach DL (1998). "The portrayal of mental illness on prime-time television". Journal of Community Psychology 25 (3): 289–302. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199705)25:3<289::AID-JCOP5>3.0.CO;2-R. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/abstract/46099/ABSTRACT?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0.

- ↑ Sieff, E (2003). "Media frames of mental illnesses: The potential impact of negative frames". Journal of Mental Health 12 (3): 259–69. doi:10.1080/0963823031000118249. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/routledg/cjmh/2003/00000012/00000003/art00006.

- ↑ Wahl, O.F. (2003). "News Media Portrayal of Mental Illness: Implications for Public Policy". American Behavioral Scientist 46 (12): 1594–600. doi:10.1177/0002764203254615. http://abs.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/46/12/1594.

- ↑ The Carter Center (2008-07-18). ""The Carter Center Awards 2008-2009 Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism"". http://www.cartercenter.com/news/pr/mental_health_fellows_2008_2009.html. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ The Carter Center. ""The Rosalynn Carter Fellowships For Mental Health JournalisM"". http://www.cartercenter.com/health/mental_health/fellowships/index.html. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ The Carter Center. ""Rosalynn Carter's Advocacy in Mental Health"". http://www.cartercenter.com/health/mental_health/rc_advocacy.html. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA (September 1999). "Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance". Am J Public Health 89 (9): 1328–33. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1328. PMID 10474548. PMC 1508784. http://www.ajph.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10474548.

- ↑ Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, Stueve A, Kikuzawa S (September 1999). "The public's view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems". Am J Public Health 89 (9): 1339–45. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1339. PMID 10474550. PMC 1508769. http://www.ajph.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10474550.

- ↑ Elbogen EB, Johnson SC (February 2009). "The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66 (2): 152–61. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.537. PMID 19188537.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Stuart H (June 2003). "Violence and mental illness: an overview". World Psychiatry 2 (2): 121–124. PMID 16946914.

- ↑ Brekke JS, Prindle C, Bae SW, Long JD (October 2001). "Risks for individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community". Psychiatr Serv 52 (10): 1358–66. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.52.10.1358. PMID 11585953. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11585953.

- ↑ Linda A. Teplin, PhD; Gary M. McClelland, PhD; Karen M. Abram, PhD; Dana A. Weiner, PhD (2005) Crime Victimization in Adults With Severe Mental Illness: Comparison With the National Crime Victimization Survey Arch Gen Psychiatry. 62(8):911-921.

- ↑ Petersilia, J.R. (2001) Crime Victims With Developmental Disabilities: A Review Essay Criminal Justice and Behavior, Vol. 28, No. 6, 655-694 (2001)

- ↑ Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, Robbins PC, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Roth LH, Silver E. (1998) Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry. May;55(5):393-401.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M (August 2009). "Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis". PLoS Med. 6 (8): e1000120. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120. PMID 19668362.

- ↑ Taylor, P.J., Gunn, J. (1999) Homicides by people with mental illness: Myth and reality British Journal of Psychiatry Volume 174, Issue JAN., 1999, Pages 9-14

- ↑ Solomon, PL., Cavanaugh, MM., Gelles, RJ. (2005) Family Violence among Adults with Severe Mental Illness. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, Vol. 6, No. 1, 40-54

- ↑ Chou KR, Lu RB, Chang M (December 2001). "Assaultive behavior by psychiatric in-patients and its related factors". J Nurs Res 9 (5): 139–51. PMID 11779087.

- ↑ B. Lögdberg, L.-L. Nilsson, M. T. Levander, S. Levander (2004) Schizophrenia, neighborhood, and crime. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110(2) Page 92.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 Brüne M, Brüne-Cohrs U, McGrew WC, Preuschoft S (2006). "Psychopathology in great apes: concepts, treatment options and possible homologies to human psychiatric disorders". Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30 (8): 1246–59. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.09.002. PMID 17141312.

- ↑ Fabrega H (2006). "Making sense of behavioral irregularities of great apes". Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30 (8): 1260–73; discussion 1274–7. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.09.004. PMID 17079015.

- ↑ Lilienfeld SO, Gershon J, Duke M, Marino L, de Waal FB (December 1999). "A preliminary investigation of the construct of psychopathic personality (psychopathy) in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)". J Comp Psychol 113 (4): 365–75. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.113.4.365. PMID 10608560. http://content.apa.org/journals/com/113/4/365.

- ↑ Moran M (June 20, 2003). "Animals Can Model Psychiatric Symptoms". Psychiatric News 38 (12): 20. http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/38/12/20.

- ↑ Sánchez MM, Ladd CO, Plotsky PM (2001). "Early adverse experience as a developmental risk factor for later psychopathology: evidence from rodent and primate models". Dev. Psychopathol. 13 (3): 419–49. doi:10.1017/S0954579401003029. PMID 11523842. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?aid=82066.

- ↑ Matthews K, Christmas D, Swan J, Sorrell E (2005). "Animal models of depression: navigating through the clinical fog". Neurosci Biobehav Rev 29 (4-5): 503–13. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.005. PMID 15925695.

Further reading

- Atkinson, J. (2006) Private and Public Protection: Civil Mental Health Legislation, Edinburgh, Dunedin Academic Press ISBN 1903765617

- Hockenbury, Don and Sandy (2004). Discovering Psychology. Worth Publishers. ISBN 0-7167-5704-4.

- Fried, Yehuda and Joseph Agassi, (1976). Paranoia: A Study in Diagnosis. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 50. ISBN 90-277-0704-9.

- Fried, Yehuda and Joseph Agassi, (1983). Psychiatry as Medicine. The HAgue, Nijhoff. ISBN 90-247-2837-1.

- Porter, Roy (2002). Madness: a brief history. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280266-6.

- Weller M.P.I. and Eysenck M. The Scientific Basis of Psychiatry, W.B. Saunders, London, Philadelphia, Toronto etc. 1992

- Wiencke, Markus (2006) Schizophrenie als Ergebnis von Wechselwirkungen: Georg Simmels Individualitätskonzept in der Klinischen Psychologie. In David Kim (ed.), Georg Simmel in Translation: Interdisciplinary Border-Crossings in Culture and Modernity (pp. 123–155). Cambridge Scholars Press, Cambridge, ISBN 1-84718-060-5

External links

- NIMH.NIH.gov - 'Working to improve mental health through biomedical research on mind, brain, and behavior', National Institute of Mental Health (United States)

- NIMHE - 'Responsible for supporting the implementation of positive change in mental health and mental health services', National Institute for Mental Health (United Kingdom)

- International Committee of Women Leaders on Mental Health – an international body of women political leaders founded by the World Mental Health Federation to produce positive change for citizens who struggle with mental illnesses.

- Mental Disorder In Old Age

- Psychology Dictionary

- Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

- Mental Illness Watch

- Metapsychology Online Reviews: Medications & Psychiatry

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||